Natalia has brought along some old photographs to share. Despite being uprooted so many times in her life, these images have always followed her. Momento mori, constants in the shifting tides. The first image shows a bright red metallic snow scooter, her behind the handles, the bright sunshine reflecting off the snow. It is taken high up above the village, on a seasonal ice fishing expedition, a favourite pastime in spring. The catch could be eaten fresh, frozen, smoked or perhaps pickled. Another image captures Natalia driving a different scooter, with her husband Sergei smiling behind her. Both are cocooned by layers protecting them from the bracing wind that blows unhindered across the high plateau landscape. Exposed skin is burnt by the wind and sun, kissed by the strong glare from the Arctic sun in springtime. An older image depicts her father, strikingly handsome, complete with a high fur hat with outstretched arms. A bear cub in each hand held by the scruff of the neck. He is surrounded by smiling children who look on in amazement. He was a ranger and trapper and kept a detailed catalogue of the wildlife and nature he encountered, describing what he saw for decades. His daughter now has his notebooks and adds information and keeps hold of that tradition. Soon she will pass them on to her son, and Natalia hopes the cataloguing will continue. In another image, she is around two years of age, looking away from the camera, shy even then. In the background, multiple animal hides, evidence of her fathers skills as a hunter.

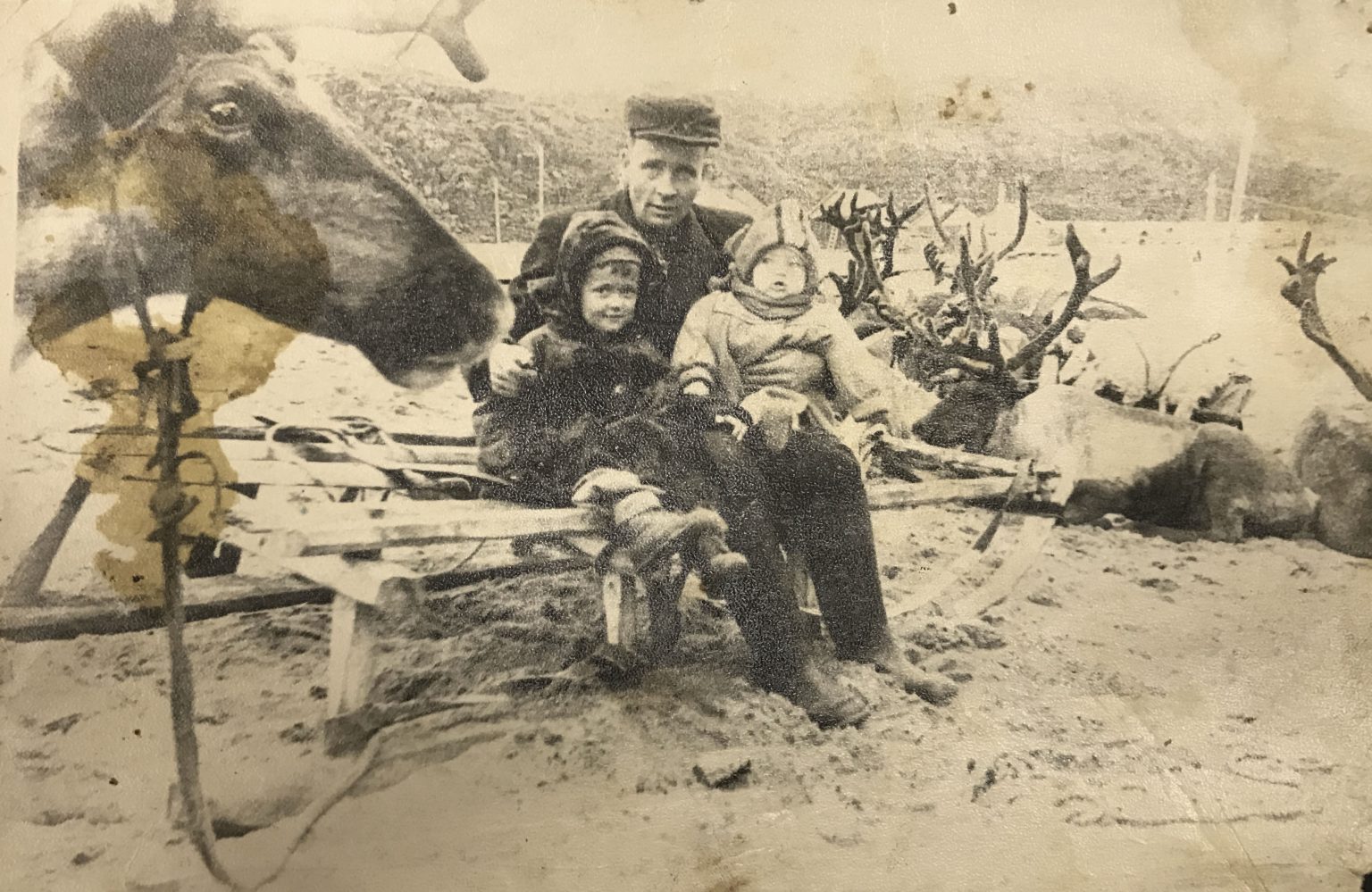

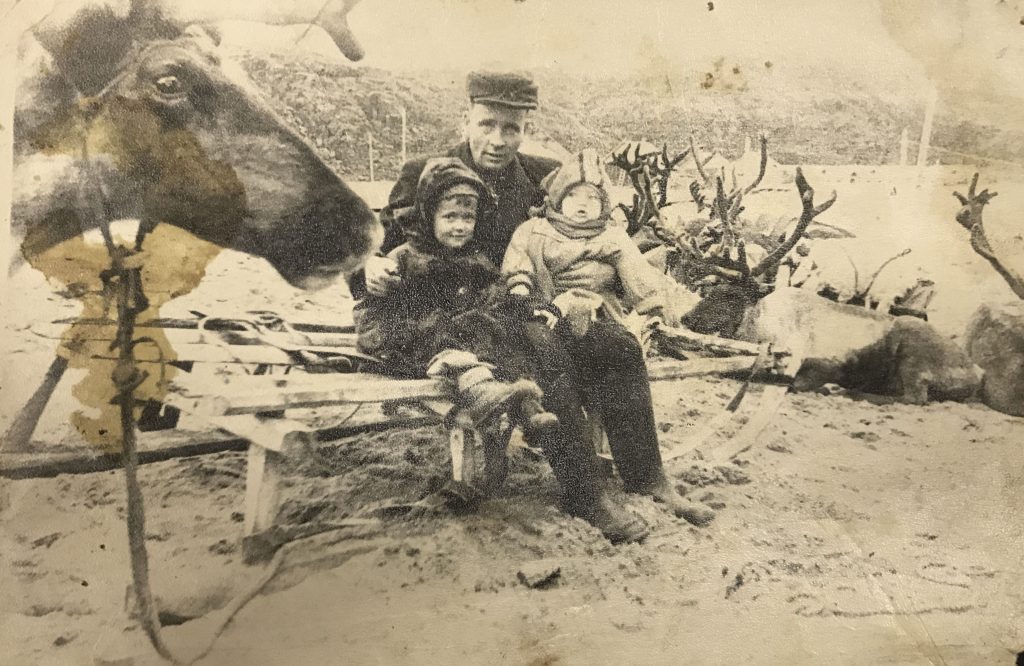

The next photo takes me by surprise. She may be age four, and another child sits with a man, surrounded by reindeer. She explains that she was quite young when her parents passed, and she and her siblings were welcomed by the Sámi community that lived in the area. Here, the late 1950s and 1960s were periods of extended hardship. People had little, but they shared whatever little they had. When the Sámi slaughtered reindeer, they gave to those who were hungry, and when the fishers had plenty they shared with the rest of the community. Exchange, trade, good neighbours, kindness and caring. There was an instinctive sense of collective responsibility for everyone, and this was part of being and living in a small place. Her affinity and understanding, respect and curiosity for land and nature in the surrounding area was forged in the beginning from these two key formative relationships. A sense of place, a sense of timeless solidarity, community, connectivity with a landscape and understanding and respect for all things in nature and those that use it. The land that surrounds us is a palimpsest. The passion and compassion for the irreducible essence of the space, and her unapologetic connection to nature and land are at her core.

Before departing from Teriberka, she hands me a large jar full of tiny bronzed fish swimming in a briny glass sea, another stuffed with pale cod tongue, a jar containing deep purple blueberry jam, fruit she collected in the summer further up the river near her Dacha, her home for the summer, and another jar stuffed with vibrant saffron coloured cloudberry jam from a nearby mountain. A palate of colour, textures, aromas and flavours gathered in nature throughout the year. Next visit, a small jar of homemade cheese, some pastries stuffed with home-caught halibut and others stuffed with her pale homemade soft cheese, using milk from the local dairy herd. The farm, now privately owned, is one of two that were established as collective farms during the communist era. In exchange I give strong black tea, butter biscuits, pungent cheese, chocolate and some dried fish, reindeer heart and beef. This trading of cornucopias reflects our differences and similarities, and our desire to use food as a vehicle for storytelling, coming together and sharing.

A season has passed and we meet again. This time she has moved again, or rather been removed. We stand in her now-vacated home. A melancholic mood is palpable and I try to understand what memories she is reliving. She moves through the house visibly becoming drained by the emotion that the place holds for her. The building was dangerous and they had to move, they were told. It will be pulled down. She and another woman in the village approached the authorities and asked to buy the building they wanted to continue to live in. “No, impossible, it was too unsafe for habitation, it must go.” Yet subsequently the authorities rented some of the apartments to tourists. Natalia had, in a previous role, worked as a building inspector and understands the structural materiality of these buildings well. They could have been repaired. There is no need to terminate their life and raze them to the ground.

Diggers and construction machinery appear periodically in areas around the village and tear down these silvered wooden relics. Alternatively they are set alight by accident—a convenient, effective, but brutal method of eradication. If the buildings remain and fall into further disrepair, they further compound the sadness. If repaired, they breathe again. If erased, the memories will fade as a new scheme is begun. Most of this work is scheduled to be undertaken as part of the beautification of the place, to encourage the much-anticipated tourist boom. The previous buildings and memories are buried forever under the foundations of the new tourist infrastructure and tarmacked roads.

Standing at the door of a garage, a small composition of maybe five units. The door is unlocked, and the unit is like Aladdin’s cave, stuffed with memorabilia. She hands me an old iron, a gift for the museum in Vardø, and an old oil lamp for myself. She pulls out some old tools and her arms swiftly cut through the air, taking form, completing invisible tasks to demonstrate function. Further back in the shed are plastic containers up-cycled as plant pots, garden tools, stakes, string, and then she throws open a door to the outside world. A verdant garden, tall foliage of potatoes in neat rows, opposite raspberry canes standing upright, laden with ripening fruit destined for the jam pot and freezer. At her dacha, five kilometres upstream from the village, she grows many additional crops during the summer. Most of her free time is spent there with Sergei.They relax, make repairs, fish, bathe, garden and hunt. That space in the tundra forest, she feels, is truly theirs. No one comes to disturb her and she can absorb the nature around her. The conversation turns to family and memory, and I explain that I live on a farm in rural Ireland that belonged to my family for five generations, yet have never lived there for longer than six months at a time. But it is somehow part of me, in my essence, my DNA. It soothes and comforts to be part of the place, where the drumlins in the landscape comfort and sustain. They are imbued with the memories and a sense of place, longing and belonging. She asks to see images, we discuss my landscape, history, nature and place. The conversation always flows easily, though it is painful at times, respectful and informative for both of us.

“Before it can ever be a repose for the senses, landscape is a work of the mind. Its scenery is built up as much from strata of memory as from layers of rock.” – Simon Schama

A small plot in the village near the garage is our next destination. This narrow strip of land, she relays to us, sweeping down to the Teriberka river, she has been allowed to buy after many years of discussion with the administration. When they do come up formally for sale, most of the land parcels are snapped up by city investors from Moscow, St. Petersburg and occasionally neighbouring Murmansk. These prime filets ripe and aged for development are earmarked as construction sites for lucrative tourist infrastructure. Many locals have also tried to buy land in the old village and have failed. Her success likely owes something to her dogged determination and unwillingness to accept no as an answer. She knows owning this land, building her own house, is the best way to take control of her home and put down roots that are not so easy to shift and move on again to fulfill someone else’s agenda. She and Sergei will gather materials from some of the condemned buildings, including her previous homes in the village, and use these to build her future home.

We meet outside her new apartment in Lodeinoe—a brightly coloured building built on the abandoned foundation of a previous development. The foundations were set in marshland and continue to shift and sink as they are absorbed by nature. The top floor has water ingress and only the middle sections are stable. The outlook for the front of the apartment is the school and playground, but her apartment faces to the back. The vast seascape from her previous home has been traded down to a view foreshortened by a sheer bank of rock. By contrast, it is oppressive, dominating and dark. She spends as much time as possible at her dacha, working in her garden or out on the sea, not wanting to be in her new home. At least the halls are filled with familiar faces and work colleagues from the Culture Palace and elsewhere in old Teriberka. The friends are all swaddled against the Arctic winter, laden down with plastic bags, chatting outside the building and in the local store. They have each other and this is what makes things much better. Having lost their homes and been uprooted from their original villages, they see familiar faces and swap stories, and share information about their daily comings and goings.