As children, when it came time to move from town to our summer place, you had better believe my grandfather made us hustle! And during berry picking season, too, there was a small window when the water level in Rigolet was optimal to ensure we could get ashore and unload our supplies. As we approached the island, my grandfather had us perch at the bow to watch for rocks so he could navigate to shore. He wanted us to remember the rocks so we could navigate ourselves when we became adults. What happens when sea levels rise and those rocks become submerged?

Climate change is threatening life across Inuit Nunangat. Insufficient snow, for example, has numerous knock-on effects: seals struggle to burrow their birthing dens and their pups risk hypothermia; their decreased numbers reduces our access to seal meat and skins for clothes or for selling, upsetting people’s preparedness for the next winter. In Rigolet, the fight against climate change is palpable, and Rigolettimiut experience the effects of negligent climate policy more intensely than people in the South might imagine.

This past decade, the controversial construction of the Nalcor Muskrat Falls Hydroelectric Project on the Churchill River inland from Happy Valley-Goose Bay and Rigolet has jeopardized our community’s well-being. Despite large local protests against its construction, Rigolettimiut now question whether we can harvest from the ocean at all because of the threat of poisonous methyl-mercury leeching from the land flooded by the dam. The political response to our concerns has been dismissive—for example, the MP for St. John’s East, Nick Whalen, tweeted in October 2016, that Indigenous people should “eat less fish” as a solution to the crisis.

These events have galvanized the artists of Nunatsiavut, raising questions of how, in this time of climate upheaval, can Inuit artists act as guides in this rapidly changing environment? I am an artist myself, and watching the Muskrat Falls protests over Facebook profoundly affected my art and outlook. My own family members were arrested protecting our lands and waters, and not being able to join them on the frontlines was agonizing. But I realized, as an artist, I have a voice and I would try my best to use it. In response to the destruction promised by the Muskrat Falls development, I painted Methylmercury (2017) and sold giclée prints of it to raise money for the land and water protectors.

It has been 23 years since I moved to Ottawa, ON, and though I have been lucky to return frequently, I am not confident in my knowledge of Rigolet’s current climate. I called a few friends and family to ask about how their artmaking has been affected by the threats against our water. As we spoke I realized we are connected through our parallel experiences—our love of home and fear for its future.

Though photographer Barry Pottle now lives in Ottawa, he keeps ties to our community, turning his art to the challenges faced by Inuit in urban centres. He spoke of the responsibility he feels to address our polluted waterways and climate change: “What can I do, how can I enhance a conversation using art and the written word?” he asks me. “Artistic expression is one of the strongest vehicles for [these conversations], and we [creators] are some of the first to talk about it, to curate around it.” Much of his photographic work documents the effects of climate change on Inuit life, both in Nunatsiavut and for those living in southern cities, looking closely at the colonial effects on food justice and security.

Sculptor Derrick Pottle, Barry’s brother, documents hunting scenes in his work, a fundamentally politically-charged subject. Derrick, who still resides in Rigolet and lives largely on the land, underlined how an interventionalist attitude from government, industry and anti-fur celebrities have profoundly disturbed the environment and Inuit ways of life:

People still feel fit to come in to disrupt people’s lives, and they face no consequences. At the end of the day we’re still here, it’s our home and where we belong. But we’re losing our culture faster than what we really think we are. And that’s enhanced by these projects, disrupting people’s ways of life.

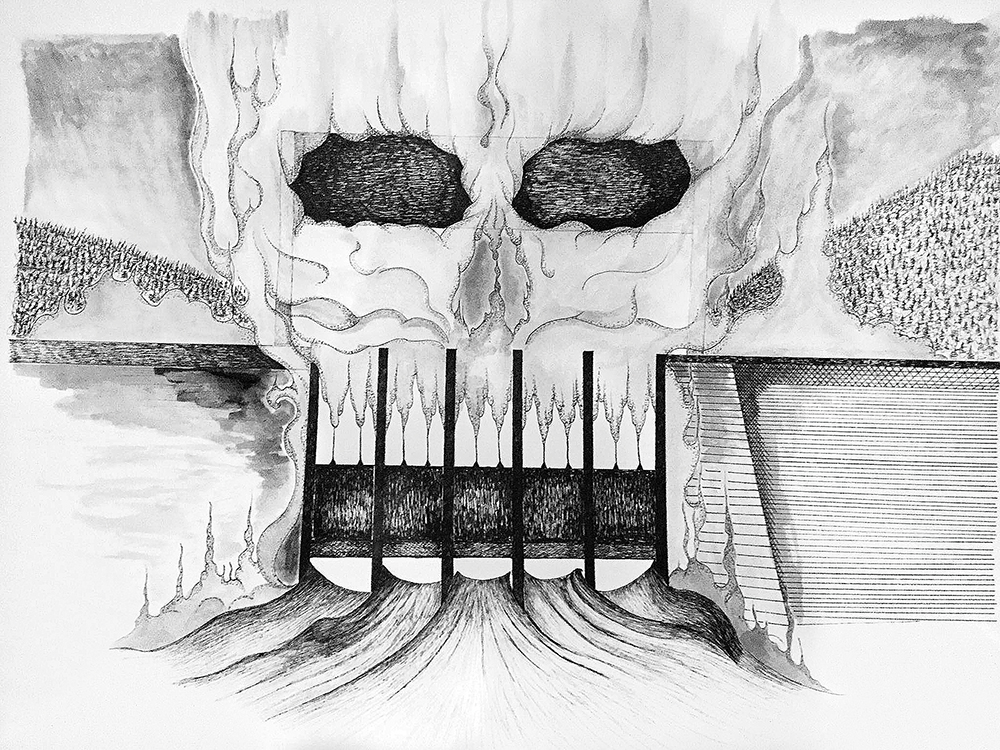

While Barry’s photographs and Derrick’s carvings often highlight what’s missing in the world’s climate response, Jason Sikoak—an artist working in mixed media, drawing and linocut printmaking—has given a monstrous face to the threats of climate change, which can often feel invisible. His drawing, Death of a River (2017), characterizes the Nalcor dam as death itself: “Seeing the images on Facebook of protesters and pictures of this damn dam, and it just looked to me like monster teeth, like a skeleton,” they tell me of their inspiration. “The dam is killing everything. It’s upping the levels of methylmercury and that’s going to be in our food source, killing us all. And all for a few dollars.”

Unafraid of offending, Sikoak draws to incite action. They were commissioned by a Muskrat Falls protestor to draw Here’s Your Economic Growth Motherfuckers! (2017), which imagines capitalism as a bio-mechanical monster, “raping the world,” Sikoak explains. “Somebody once asked me, ‘Aren’t you worried your art will be taken as rude?’ and I said, ‘Well, if it gets the point across, I don’t care.’”

Back in Rigolet, textile artist Inez Shiwak’s artistic and community work attempts to address these issues at ground-level, building networks and tools to help residents adapt to the fragility of a changing environment.

She refrains from representing climate change out of respect for the other Rigolet artists who have made it integral to their work. She instead focuses her activist energy in her community work in the arts industry, previously as an administrator of the Rigolet Digital Storytelling Project and as a researcher for the eNuk app—a platform that aims to be “an integrated environment and health monitoring program designed by, with, and for Inuit in Rigolet.”[1] The app represents, in microcosm, the need for us all to work together to bring awareness to climate change. It aims to collect knowledge from community members to accurately track the effects of climate change, and issue warnings that can help improve the health of individuals within the community.

In Rigolet, art and climate are woven into the fabric of this close-knit community, and there are many more artists who continue to use their work to comment upon the challenges we face today. Whether they are creating sculptures, or textiles, documentaries or climate change data, we all share a common goal: protect our land and our way of life, understanding that it also means protecting the planet as a whole. When we—as Inuit, artists, and Rigolettimiut—say everything is interconnected, I hope you have a better idea now of what that means. I hope that you are listening, and are asking yourselves, “How can I help?”

NOTE

[1] For more information on the eNuk app, visit: https://enuk.ca/

Author biography

Heather Campbell is an art consultant and artist from Rigolet, Nunatsiavut, NL, now based in Northwest River, NL. She has a BFA from Sir Wilfred Grenfell College School of Fine Arts, Memorial University, and has worked as a Curatorial Assistant at the Indigenous Art Centre of Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC) in Gatineau, QC, and the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa, ON. She is the Strategic Initiatives Director at the Inuit Art Foundation.

Credit: This article was originally published by the Inuit Art Quarterly on June 15 2020. Copyright the Inuit Art Foundation.