Curated by Tania Wilard, it became the striking visual for LandMarks2017, a monumental, multi-site project undertaken by a curatorial team from across the country and realized in and around Canada’s national parks and historic sites. Shortly after, Gruben’s work graced the cover of C Magazine’s Winter 2018 issue, kicking off what is sure to be a notable year for the artist. Despite this seemingly rapid rise, however, Gruben has been steadily creating a body of work that is characterized by its methodical and undeniably intimate materiality.

Born and raised in Tuktuyaaqtuuq (Tuktoyaktuk), Inuvialuit Settlement Region, NT, Gruben spent much of her childhood sewing with her mother, a seamstress, and trapping with her father. These influences appear to be self-evident in Gruben’s works, which generously feature sealskin, polar bear fur and moose hide. In many of her works, however, these organic materials are joined by wax, reflective tape, steel grommets and latex, resulting in objects that leap beyond their discrete visual vocabularies into a language uniquely their own. When I reached her in her studio this past April, Gruben had just finished a new piece marrying vintage military service medals with sealskin, “in honour of our hunters,” she explained [1].

Over the past several years, the artist has been making and exhibiting works that foreground hide, fur and bone and that display “an innate material intelligence,” says curator and writer Kyra Kordoski, who works closely with Gruben. “There is a foundational process of thinking through the materials themselves,” she adds [2].

An early work in this vein is This is Not a Hudson’s Bay Blanket (2015), consisting of a patchwork, moose hide blanket, carefully folded and displayed atop an aluminium plinth. Featuring layered patterning, where curving forms are butted up against tight, linear cuts, this composite work was constructed with non-uniform pieces of hide that have been stitched to one another. The material was sourced from the scraps of other textiles—mitts, moccasins, jackets, etc.—made by elders, specifically from the Sahtu Region and Fort Simpson, NT, “some of whom are very distinguished sewers, who tanned the hide themselves,” Gruben elaborates. Throughout, small slits, holes, and colour and textural variation are visible and stand in stark contrast to the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) blanket’s ubiquitous straight lines in red, yellow, green and navy. “I put [the scraps] together the way they came to me,” Gruben explains. The sensory aspect of the piece, the distinctly warm and animal smell, is also central to one’s experience of it. “The smell of moose hide brings you home, to the land, as opposed to a blanket which spreads disease,” says the artist. “I wanted this blanket to carry healing.”

Although the history of the HBC in Gruben’s home community of Tuktoyaktuk is comparatively recent (a trading post was established in the 1930s), its presence in Inuvialuit territory and the surrounding regions dates back to the mid-nineteenth century. This is Not a Hudson’s Bay Blanket signals to this long and complex history and is particularly poignant when read in relation to the MacFarlane Collection, considered to be one of the largest and best-preserved records of Inuvialuit life in the nineteenth century, including numerous items of skin clothing and sewing tools [3].

The collection, now held at the Smithsonian in Washington, DC, and comprised of some 300 Inuvialuit cultural objects, was amassed by a Fort Anderson Hudson’s Bay trading post manager in the 1860s. Only in the last decade were a group of Inuvialuit elders and youth, including seamstresses, permitted access to these objects that have been stored out of public view for more than 100 years. Gruben’s careful stitches and repurposing of materials is a poignant reminder of resiliency in the face of unimaginable loss.

The artist has similarly utilized small, cut pieces of moose hide in her 2016 piece Breath. At five feet in height, the work is a human-scaled textile work, where each piece has been affixed to unprimed canvas with an individual stitch of white thread. Reminiscent of an Agnes Martin–style muted grid, here Gruben recasts the austere structures of minimalism in favour of an undulating, slightly askew composition. What begins as delineated columns at the top and bottom are interrupted with a tightening and a wiggle in the middle, suggestive of a wrinkle or a pucker. The tautness of the outside edges pull inward toward the centre of the piece, creating strong horizontal lines across the middle, reminiscent of a hug. As a result we are pulled into—swallowed by—the work.

In Consumed (2017) beluga intestine was harvested, cleaned and dried, before being reimagined as a transparent vessel, or pocket, for the suspension of found objects: glowing red seed beads, a curled iPhone charger for an obsolete model and a yellow LifeStyles condom. Some of the objects hit heavy on first reading, such as a gold embossed My Little Bible with colour-bled edges, which hints at the collision of Indigenous knowledge and the legacy of Christian missionaries. Others, like the aforementioned beads, conjure something deeper, pushing and prodding for more consideration. Coloured glass beads, like those employed by Gruben, are widely used by Inuit seamstresses to create intricate designs on kamiik (boots), parkas and other textile pieces, but also signal the earliest moments of trade, exchange and globalization within the Canadian Arctic. The luminosity and delicacy of these small jewel-like spheres against the translucent and tangible surface of their envelope is piercing. “Beads,” writes Kordoski, “are creative tools. [They are] potential grains of storytelling— generative means of strengthening, adorning, celebrating and expanding the fabric of a culture” [4].

Objects are similarly suspended, encased, venerated and pre- served in the work of Anchorage, Alaska–based Sonya Kelliher-Combs. In Remnant (2016), however, the structure is inverted. First exhibited at SITElines.2016 much wider than a line, the SITE Santa Fe Biennial, Kelliher-Combs’ Remnant takes the form of small, wooden boxes, wrapped in tinted, semi-opaque acrylic polymer “skins.” Each frame plays host to a small piece of vibrant organic matter, pulled largely from the artist’s personal collection—a caribou antler, a length of seal intestine, the delicate, feathered wing of a bird. As art historian David Winfield Norman notes, behind the “sheen of the synthetic skin, [the objects] take on a dreamlike quality and begin to appear somehow, mysteriously, alive” [5]. They, like much of Kelliher-Combs’ work, also reveal and obscure narrative—they remember. Secrets and stories, memory, exchange and history are foundational to the artist’s practice and are transmitted by way of her choice of embodied materials, which regularly include hair and animal skins, fur, guts and intestines.

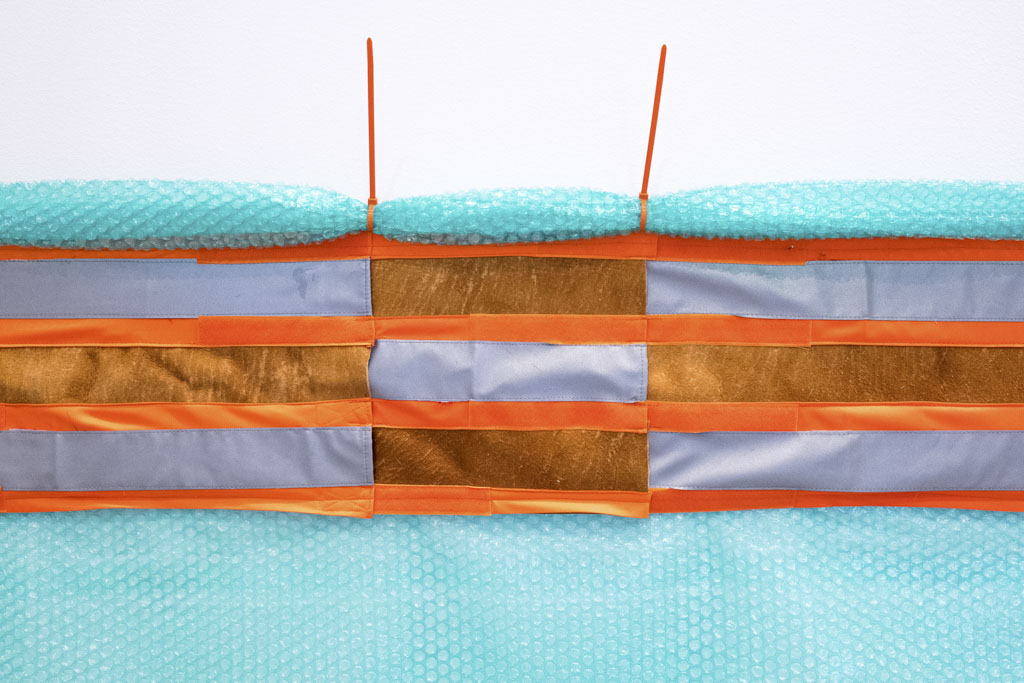

Often, the narrative aspects of Kelliher-Combs’ work reveal or release stories of deeply rooted trauma. One such series, Idiot Strings, which includes both two- and three-dimensional works, was created largely between 2001 and 2005 and is a testament to the immense, intergenerational impact of suicide in small northern communities. Notably, the first four works in the series were created in memory of members of Kelliher-Combs’ own family who died by suicide. The title of the series evokes a resistance to forgetting: “idiot strings,” as they are colloquially known, are the strings tied to children’s mittens to prevent them from losing them. This tender concept is perhaps most identifiable in the larger three-dimensional installations from the series where the mitten forms are evoked with dangling pouches, fashioned from walrus stomach, sheep or reindeer rawhide or acrylic polymer, and tethered to one another with strands of cotton rope. “The larger installations,” Kelliher-Combs explains, “relate to generations of Alaska Natives who have taken their own lives because of loss of identity, alcoholism or abuse. [The works are] also about not forgetting those things, acknowledging them and staying connected to who we are, but at the same time letting go of those painful things to be able to heal from them, move on and transform them.”

This impulse to name the wound and to let it heal runs deep in Kelliher-Combs’ practice and often includes the voices of others. For a 2007 project at the Anchorage Art Museum, Con-Census, the artist curated an exhibition of objects—hand-sewn mittens and skin boots—pulled from the museum’s vaults and paired in thoughtful arrangements, often alongside new items such as cardboard boxes affixed with the Silver Hand seal, noting “Authentic Alaska Native Art,” and identification cards.

One work titled Goodbye (2007) brought together 38 pairs of gloves on a wide, low-standing, white plinth. The arrangement—a memorial—represents the number of Alaska Natives who died by suicide, starting in 2005 and continuing up to the exhibition’s opening. “When I did Con-Census,” explains the artist, “a big part of that was to bring out things that people don’t talk about. . . . My work is not just about creating this physical thing, it’s also about what I think is missing from this world today, which is the time we spend with each other, with our families. Whether it’s learning to do something—hunting or fishing or cooking—or spending time together as a family, it’s something we need to have in our lives for enrichment, this interaction with each other. A lot of my work is about that time spent, [which is] something you can’t get back—learning from your grandma or your mom. It’s not necessarily about the object that you made afterwards, although that is the culmination of this time, it’s more about the time that you spent with somebody and what happened during that time.”

Increasingly, Kelliher-Combs’ time is spent thinking, making and discussing with others. In recent years, a major aspect of her work has been the creation of spaces of exchange and sites of dialogue with other Indigenous artists, scholars, curators and collaborators in the form of Curated Conversations. The ongoing series, begun in 2015 in collaboration with the Anchorage Museum as part of their Polar Lab series, has featured notable participants from across North America and the Global North, including Inuit photographer Barry Pottle, Greenlandic performance artist Jessie Kleemann, curator Candice Hopkins and iconic performance artist James Luna (1950–2018). Topics have included borders and boundaries, northern food security, self-determination, sovereignty and place names, and exhibiting and commodifying culture. The result, explains Kelliher-Combs, is far-reaching and ongoing “connections across geographic boundaries and disciplines.”

This collaborative, multivocal approach is also reflected in the work of Sámi artist Joar Nango, who in 2017 created an ambitious and open-ended project for the dual-site documenta 14 (Athens, Greece, and Kassel, Germany), arguably the world’s largest and most prestigious contemporary art event.

In October of 2016, Nango travelled north from his home in Tromsø, Norway, to a remote valley near where his uncle and grandfather, both reindeer herders, had kept their summer pasturing grounds. The area is a significant site of harvest for the natural materials traditionally used by Sámi herders to build temporary structures and holds a particular interest for Nango, a trained architect. “Because it is such a steep, north-facing slope, all the birch trees that grow there have this special frame, this bent shape,” explains the artist. “Those bent trees are a very valuable building material in Sámi tradition; they are called bealljek, and they are used as the primary structure for both our tents and our turf houses.” After identifying 12 similarly sized trees, Nango felled and dried them for several months, before loading them into his red 1996 Mercedes Sprinter. Outfitted with a large freezer, filled with two reindeer he had slaughtered— half of the meat smoked, the other dried by the artist’s aunt—Nango’s van was also packed with 38 reindeer skins collected en route to Athens.

Nango’s resulting work, European Everything (2017), is simultaneously an installation, a stage, a performance and a site (or rather sites) of encounter and collaboration. Crucially, it is also the action-based journey made by Nango, with all of his tools and materials, from Tromsø to Athens to Kassel and back again. “I started with the idea of bringing something, or some things, that are very meaningful and very representative of my home, when I started the journey. I guess those are the materials I thought about as representative—the birch, the meat and the skins. Everything else I left open to chance and to the production phase in Athens.” As Nango drove south to Athens, he continued to amass materials from across the continent. “I wanted to investigate this slice of Europe in a way,” he says. “I wanted to check out, what is Europe as a piece of land? What is Europe without its borders? What is Europe as you move through it, and what can it be for me in the way that I think about the world, space and identities?” Nango’s production phase took place in a local scrapyard, becoming his temporary studio for the three months leading up to documenta’s April 2017 opening.

European Everything was installed in the outdoor courtyard of the Athens Conservatoire, becoming both an installation as well as a collaborative venue, including performances by Greenlandic DJ Uyarakq and rapper Tarrak, yoiker Wimme Saari and others. The main structure, built from Nango’s birch trees, was constructed by the artist alongside local refugees, while the canvas for its surrounding was culled from the discarded awnings of local businesses. The interior was outfitted with a soft, fur-covered base. Traditionally, the floors of Sámi tents are made with a thick layer of tender, spring birch branches atop which reindeer skins are placed. The result is a “very luxurious” mattress-like construction, made fragrant by the birch trees’ new leaves, explains Nango. For Athens, olive branches were substituted to create a cushion, while the covering became a mix of reindeer and sealskins, the latter procured by the artist on a trip to Greenland. The stage, a monumental letter E, was constructed from an old sign for Eskimo, the brand name for home appliances produced by Viometal Eskimo, a now defunct Greek company. The original neon tubing from the sign was also repurposed for the installation, made new in glowing blue and suspended alongside speakers wrapped in sealskin. The assemblage speaks to the resourcefulness and improvisation of an Indigenous built environment, particularly one that exists “where resources are scarce and the climate unpredictable, harsh and unmerciful” [6].

For the opening in Kassel, Nango was asked by the documenta 14 curatorial team to create a lectern for the official press conference. In response, Nango built a sculptural composite that included Serbian animal tails, chairs found on the street in Athens, a gravestone from Sweden, neon from the Athens installation, marble from Serbia and copper from Romania—“all these different European materials I had gathered, I manufactured into this strange little lectern.” Absent from the final iteration was a sealskin pelt, removed at the request of the curatorial team, who worried its presence would become a catalyst for criticism and detract from the main focus of the presentation. In its place, Nango included a silk, Picasso-inspired jacket from Berlin. When asked about the switch, Nango explains that after his initial anger at the request subsided, what became most interesting was his own position as a Sámi artist. “I think if it had been a reindeer skin, I would have felt a stronger connection to it. Maybe I would have felt differently if I were Inuit, maybe I wouldn’t have compromised.” What the incident ultimately revealed, is the capacity for a quotidian Indigenous material, one that is entwined with Inuit survival, livelihood and culture, to act as a major global disruptor. Likewise, Nango’s reindeer skins proved difficult for his Athens audience to ignore—six were stolen from the installation during the exhibition’s run.

In 2016 Nango’s ongoing research on circumpolar architecture brought him to Iqaluit and Kinngait (Cape Dorset), NU, where he looked at the legacy of government-built dwellings in the Canadian Arctic. The resulting installation, Folding Forced Utopias, for you, was exhibited at Gallery 44 in Toronto, ON, and featured, among other components, a cut sealskin, screen printed with “The government is the owner of the house. . . . Eskimos rent houses from the government.” The line is pulled from the manual Living in New Houses (1970), published by the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development (now Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada), a photocopy of which was placed atop a reindeer skin nearby. The installation also includes an oversized light box, depicting a collection of cardboard, kamik-pattern pieces, cut from cereal and cracker boxes atop which is placed cut pieces of reindeer leg skin, used in the making of nuvttohat, the iconic, curled-toe, fur boots heavily associated with Sámi culture. Although the repurposed kamik templates are perhaps unlikely markers of culture on first pass, they carry within them the knowledge of generations of seamstresses in the making of garments and the will and ingenuity of passing that information forward, in whatever form or material might be available.

“I use what’s available to me.” That is what Maureen Gruben tells me halfway through our call when I ask about her choice of materials. It is a seemingly simple statement with profound roots and real impacts. For Gruben, as well as for Kelliher-Combs and Nango, what is available are materials that are deeply personal and intrinsically political, circulating far beyond the discrete control of the artists themselves. This is clear from the strong, affective responses they elicit, including “morality” legislation that bans or restricts the import of certain organic materials, including animal bone and skin, across international boundaries, and from the explosive and much-publicized rhetoric of anti-sealing groups [7]. For Gruben, growing anger towards the anti-sealing movement and its disregard for the impact on Indigenous life and culture hit its breaking point in the creation of her 2018 piece FUK, a massive sculpture of a penis emblazoned with “#sealfie.” “Seal is so important to us,” explains Gruben. “And the time has come to just say ‘Fuck you.’”

NOTES

[1] All quotes from Maureen Gruben, Sonya Kelliher-Combs and Joar Nango, unless otherwise noted, are taken from telephone conversations with the author on April 9 and 10, 2018.

[2] Conversation with the author on April 13, 2018.

[3] CBC News, “Inuvialuit Elders, Youth to View Rare Artifacts at Smithsonian,” CBC News Online, May 19, 2009, accessed April 2017

[4] Kyra Kordoski, “Shift; Rise: Maureen Gruben’s UNGALAQ,” in UNGALAQ (When Stakes Come Loose) (Vancouver: grunt gallery, 2017), unpaginated.

[5] David Winfield Norman, “Sonya Kelliher-Combs: Iñupiaq-Athabascan Interdisciplinary Artist,” First American Art Magazine, no. 14 (Spring 2017): 58.

[6] Candice Hopkins, “Joar Nango,” online excerpt from documenta 14: Daybook, accessed April 2017.

Author biography

Britt Gallpen has been the IAQ’s Editorial Director since 2016, and oversaw a full redesign of the magazine in conjunction with the Inuit Art Foundation’s 30th anniversary in 2017 and the launch of the IAQ Profiles in 2017. In 2021 she was nominated for Editor Grand Prix at the National Magazine Awards.

Credit: This article was published by the Inuit Art Quarterly on November 20, 2019. Copyright the Inuit Art Foundation.